These translations are more than the words they contain. They have covers, in some cases illustrations, forewords, prefaces, afterwords, blurbs, dust jackets, biographies of the author, biographies of the translator – reams of ‘paratextual’ information, the name for the features of a book that support the text.

Necessarily, the process of designing these paratextual elements requires imagination, creativity, and cultural biases to bring them into being. None of the cover images shown in the ‘Illustrating Austen’ section sprang into being fully formed; all were dreamt up by specific individuals with specific cultural and personal experiences. So how, in the process of readying translations for publication, has Austen been imagined? How has she been perceived? Marketed? Domesticated? Explained?

Jump to:

- What’s in a Name? The Challenges of Naming Austen

- Covering Austen

- Introducing: Jane Austen

- Losing the Plot: A Selection of Blurbs

- Conclusion: The Incredible, Imaginary Jane

What’s in a Name? The Challenges of Naming Austen

Firstly, the issue of a name. Nowadays, ‘Jane Austen’ is instantly recognisable – it is a global brand, a cultural signifier, and a marketing tool. There are Jane Austen rubber ducks. There are Jane Austen societies in at least 10 countries worldwide. You can buy Austen T-shirts, tote bags, jigsaw puzzles, mugs, candles, pencil cases, notebooks – practically anything, with Austen’s name on it.

The first few translations were published without her name on them at all, like her original novels, which were simply titled ‘by a lady’. Indeed, Austen’s first full translator, Isabelle de Montolieu, was much more famous to a French audience than Austen was herself, so they appeared only under her name. Some subsequent translators, from Sweden to Portugal, subsequently relied only on Montolieu’s translations rather than the original texts.

But that, of course, is not the case today. The name of Montolieu has far been eclipsed by that of Jane Austen.

Therefore, in a translated text, the translator – and publisher, who after all is mostly keen to sell the book – must harness the familiarity of a big name like Jane Austen without estranging her from their readers. Indeed, as Austen is often seen as being classically or iconically English, there have long been anxieties about how foreign readers might perceive her. One early example, as Git Pipping and Eleanor Wikborg discuss in The Reception of Jane Austen in Europe, can be seen in how the first Swedish translations of Persuasion and Emma were altered to fit Swedish conceptions of ‘English lady novelists’ and their writing.1

This process of altering Austen’s works through translation to more closely align with the expectations of readers from a different culture persisted mostly in the nineteenth century. But the phenomenon of ‘domestication’ – how texts are adapted and familiarised through translation to match cultural expectations – persists interestingly in the different names given to Jane Austen by different editions.

Below is a list of the various names that she has been given, in various languages and across various time periods. They represent attempts to make a globally known name feel local and relevant to the reader. How do you make a name feel familiar yet also retain its recognisability? These translators have done their best to retain the brand and fame of Austen whilst simultaneously ‘domesticating’ her to appeal to readers.

جين أوستن

Ceyn Ostin

Джейн Остин

Jane Austenová

جین آستین

ჯეინ ოსტინი

Τζεην Ωστεν

ג’יין אוסטן

Ioanne Austen

Džeina Ostina

Jane Austen

Джейн Остен

Џејн Остин

简·奥斯丁著

Xhejn Osten

ジェーン・オースティン

Džejn Ostin

This group of languages encompasses numerous different scripts, alphabets, and syllabaries. The range of representations of her name shows the global reach of her presence in the industry. To sell an Austen novel, both the ‘Englishness’ of her brand and her relatability to readers needs to be stressed. Simultaneously presenting her as unfamiliar and familiar has led to many amalgamations of her name that try to smooth the gap between cultures.

Covering Austen

As seen on the Illustrating Austen page, the covers designed for Austen’s novels are many, varied, and imaginative. The ways they depict Austen often conflict, representing different social and cultural expectations of her writing. See below for a discussion of some of the more interesting covers, and what they might tell us about how Austen is popularly conceived.

This startling looking detail from a Romanian cover image features a glossy, sensual, woman who looks like she would not be out of place in a fantasy-romance novel. She would, however be very out of place at Netherfield Hall. It is indicative of how Austen has often been marketed as a writer of women’s romance, sold in cheap, mass-market editions that emphasise sex appeal.

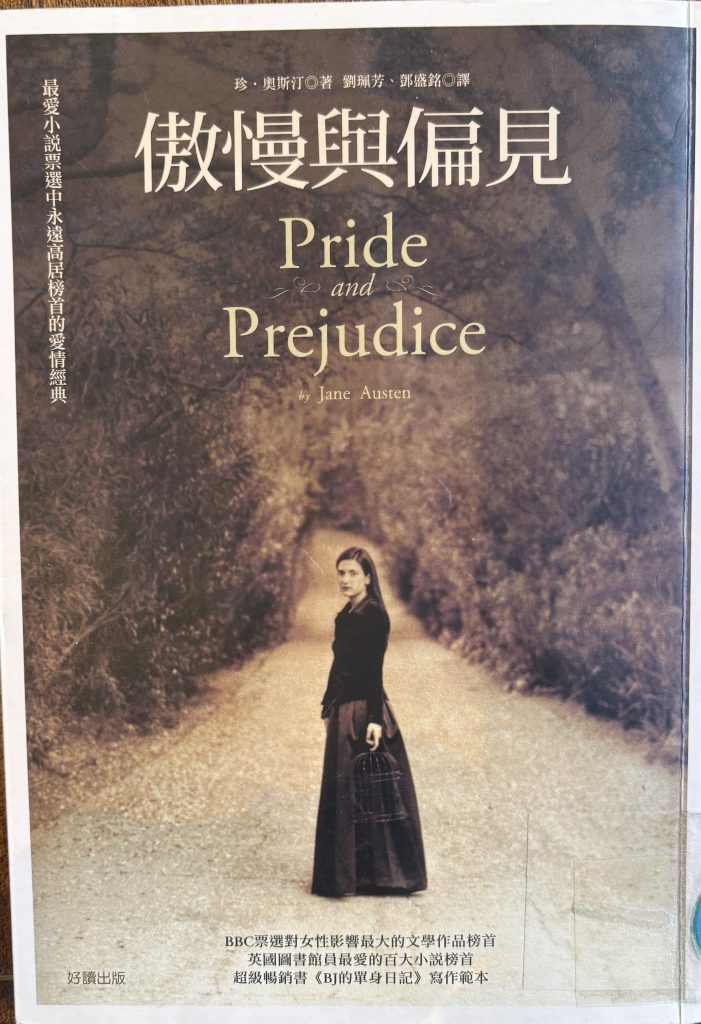

This Chinese edition is one of a few editions whose covers are reminiscent of the Victorian gothic. The spooky atmosphere and Victorian-esque photography seems a far cry from the Regency period, and curiously, the woman in the photo is holding an open birdcage. It is suggestive of the way that Austen and the Brontës came to be conflated as women writers, with popular confusion over the distinct identities of the three Brontë sisters versus Jane Austen.

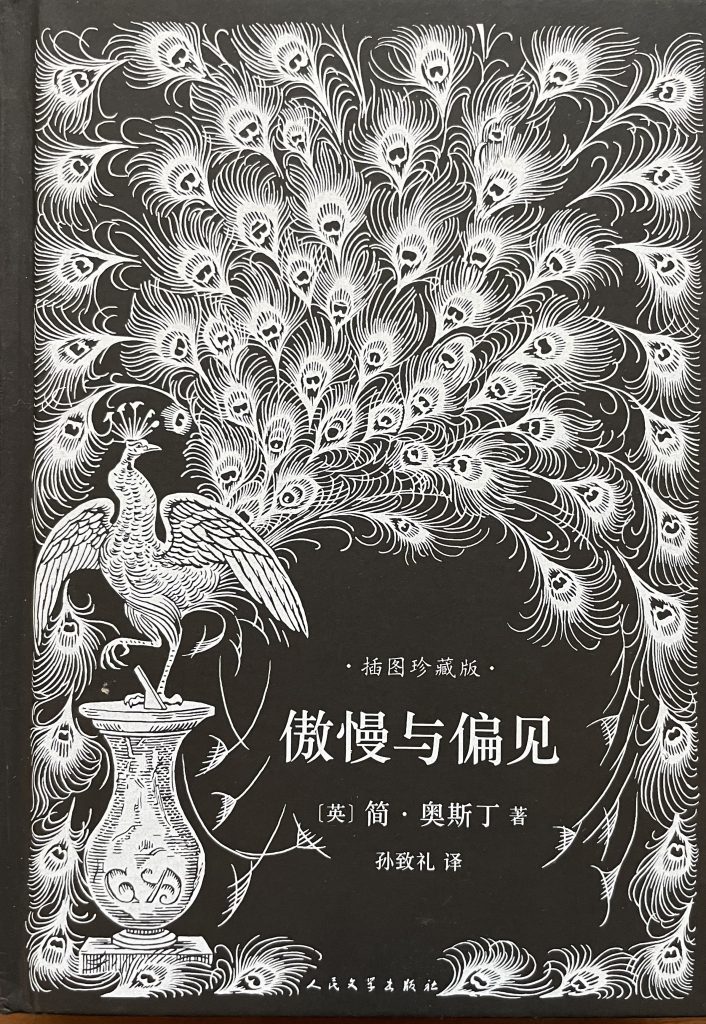

This cover represents a fascinating example of cross-cultural confusion. A commemorative Chinese edition for Pride and Prejudice‘s 200th anniversary, it uses Hugh Thompson’s classic peacock illustration, meant to indicate pride. Yet in China, peacocks aren’t associated with pride – roosters are. How far can paratextual information be said to translate between cultures? Though now the predominant image associated with the novel, it might not be read the same way in different countries and cultures.

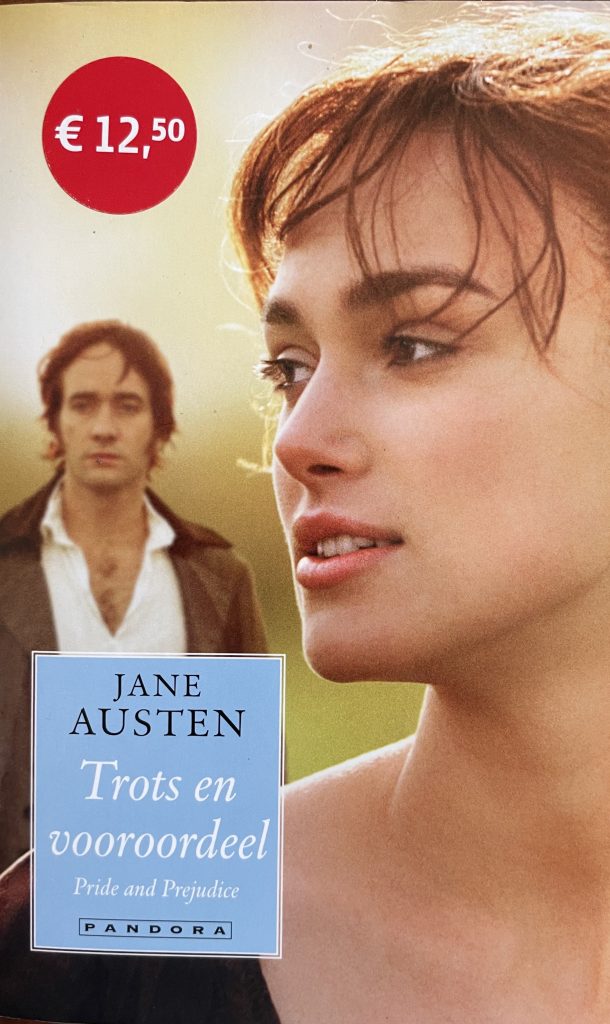

Post-2005, many (many, many) covers of Pride and Prejudice featured Keira Knightley. Interestingly, her face became a bigger marketing tool than the name of Jane Austen, and editions from the Netherlands to Serbia to Azerbaijan all carry stills from the film. The same is true for Sense and Sensibility, which after Ang Lee’s 1995 film, became heavily marketed in translation through film stills of Emma Thompson and Kate Winslet. Many editions are marketed as ‘the book behind the film’ or similar.

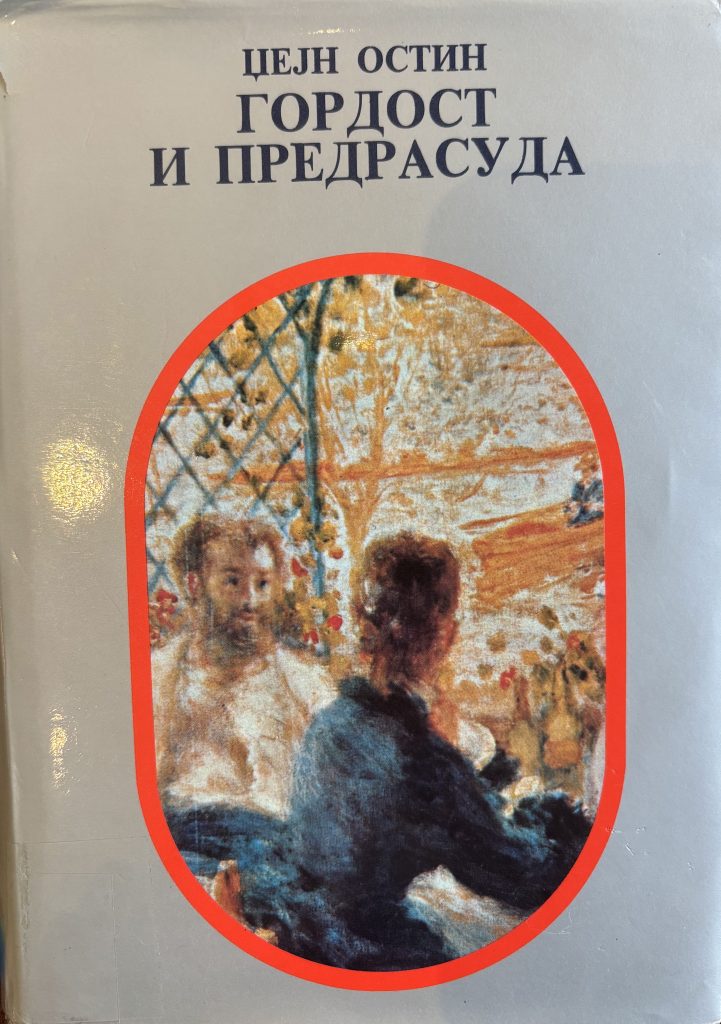

This intense looking, hardback Serbo-Croat edition has a shiny, metallic grey cover under the dust jacket, and is printed in a strong, heavy font. It looks very industrial and ‘serious’, a big contrast to, for example, the flimsy and sensual Romanian cover. It illustrates how Austen has been imagined simultaneously as a canonical behemoth, a writer of ‘great’ or ‘classic literature’, and as a mass-marketable author of cheap romance.

These are just a few of the interesting ways that illustrators and cover designers have chosen to depict Austen. Crucially, their choices are based on not just how they imagine her, but how they imagine fans – or the literary market in general – will receive her. A quick look at the latest Penguin editions available in bookshops today will show you the strong influence of ‘booktok’ on the literary market. The new covers feature young, modernised versions of Austen’s heroes and heroines, in the bright, colourful style used by almost every popular romance book today – or at least the ones most talked about online, whether on ‘booktok’ or ‘bookstagram’. These are complemented by the Penguin ‘clothbound classics’ editions, which are reserved for great ‘canonical’ literature and are more expensive than a typical paperback. As a new Netflix adaptation of Pride and Prejudice is in the works, it will be interesting to see if a proliferation of new editions and translations featuring stills from the tv series will hit bookshops around the world.

Introducing: Jane Austen

Turning the page, then, we are left with the problem of how to introduce Austen – a writer so well known, and so thoroughly loved, talked about, rejected, misinterpreted, copied, and pastiched, as to render her true essence somewhat lost in the sum of her cultural imaginings. Many editions, as previously seen, choose to emphasise the films over the text, calling their translation ‘the book behind the film’ and providing detailed information on casts and directors.

Others are more thought provoking in their handling of prefaces, introductions, and dust jacket biographies. Here are a few examples of ways that Austen has been introduced to her global readers.

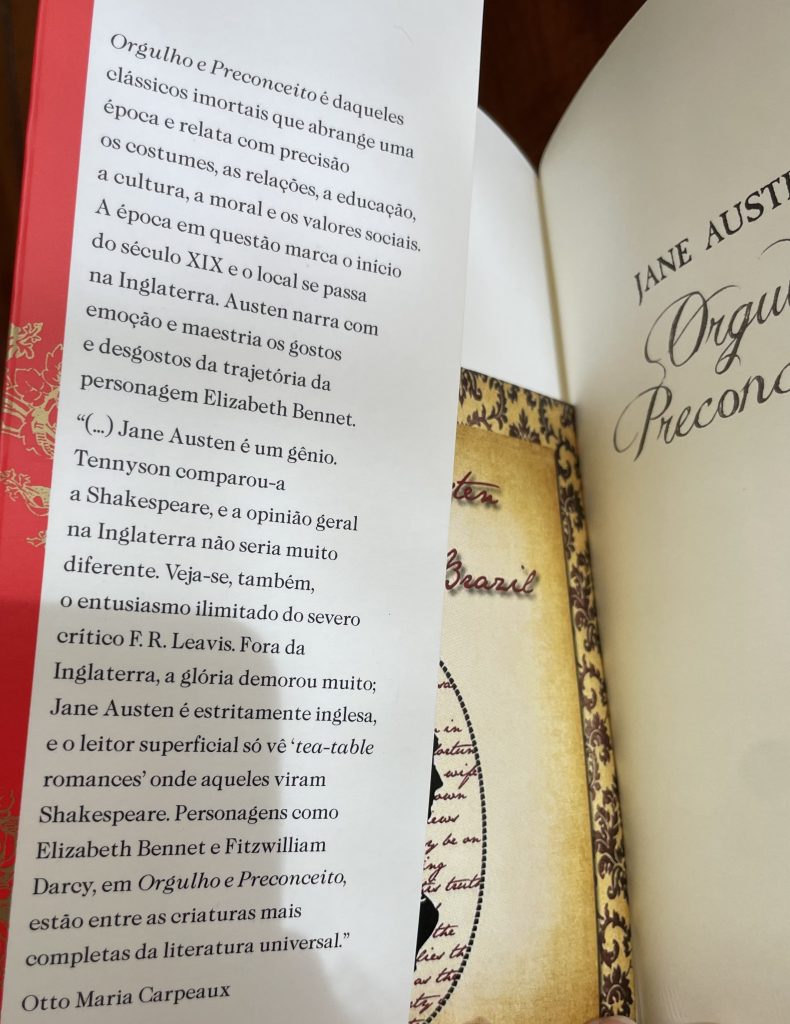

This Portuguese edition from 2012 claims that ‘Jane Austen is strictly English’, and blames global readers for long misinterpreting her works. ‘Outside England, her glory was long delayed’, it says, due to the ‘superficial’ readers, who view her works merely as ‘tea-table romances’ where ‘they should see Shakespeare’. This dismissive attitude to readers is common, especially in more academic editions.

This dust jacket biography from a 2020 Japanese translation lists Austen’s novels and describes them as ‘the pinnacle of modern British novels’. It is one of the only translations to mention Austen’s technical and stylistic skill, saying ‘she is also known for her significant contribution to the development of free indirect speech’.

Austen in Pakistan: A Case Study

Other editions are more thought provoking still in their introductions to Austen. Here are a few excerpts from the preface to an Urdu translation of Pride and Prejudice, published in Pakistan in 2015.

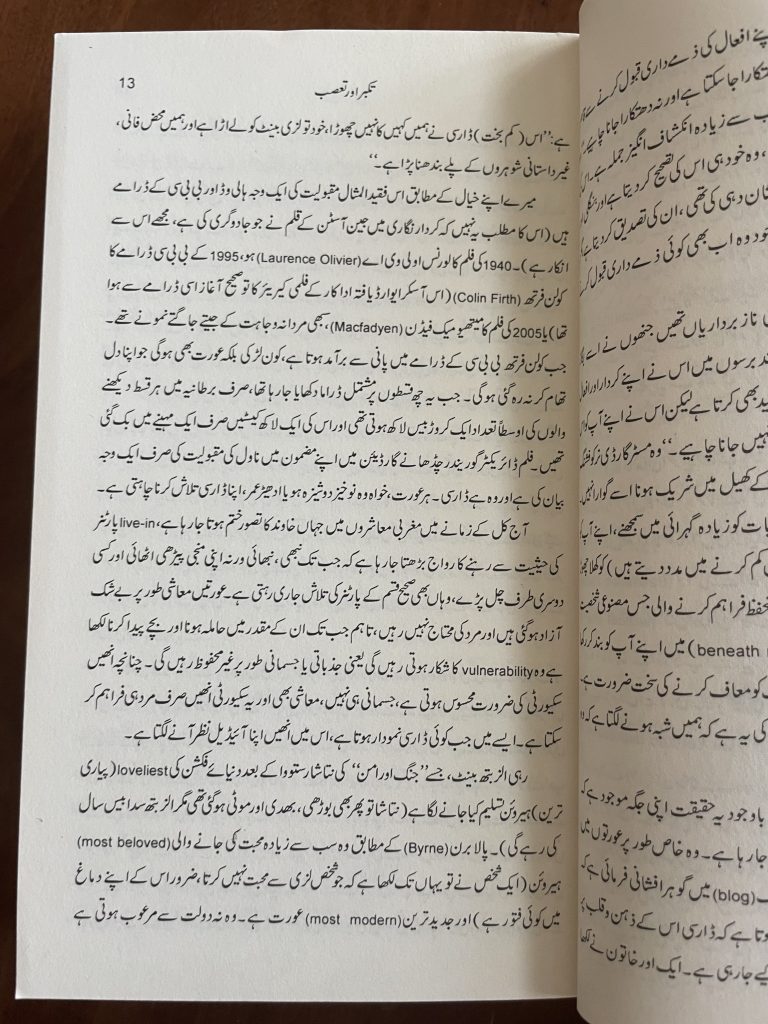

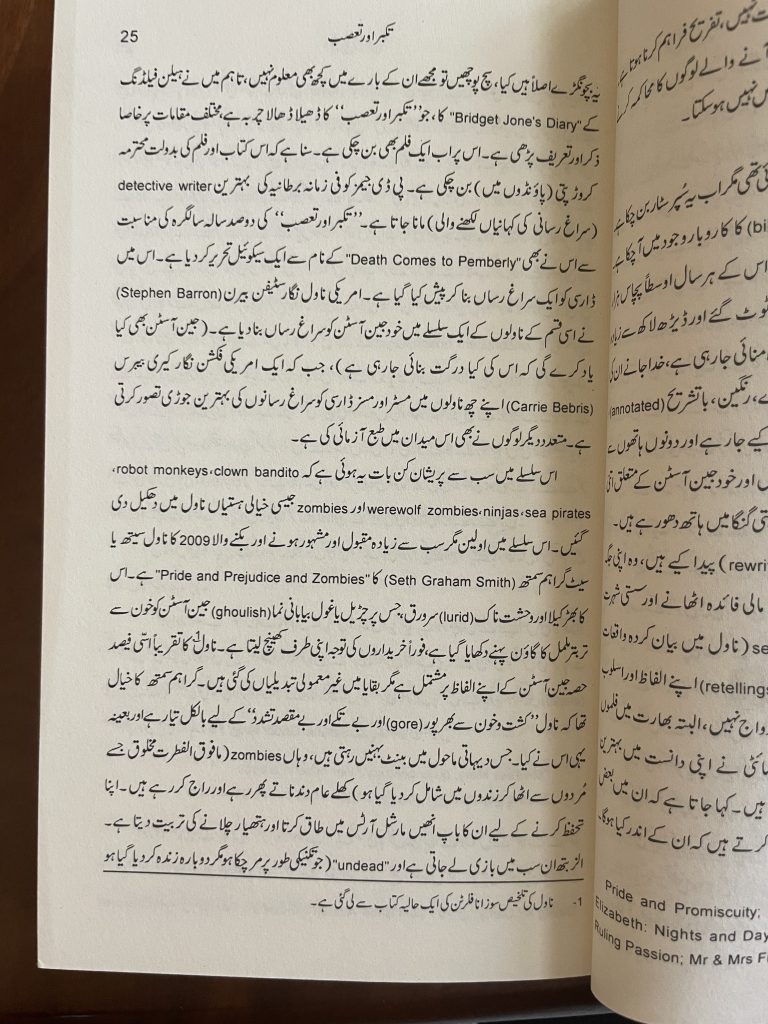

The writer clearly has strong feelings about what Austen’s novel means for readers, women in particular, and society at large. He also has strong feelings about how she has been imagined and adapted by others, particularly focusing on the book Pride and Prejudice and Zombies by Seth Grahame-Smith.

Here, translated, are a few sections from his introduction:

on why Pride and Prejudice, and in particular the figure of Mr Darcy, has been so successful with female readers:

‘Women have become economically independent and are no longer dependent on men, but as long as it is written in their destiny to become pregnant and give birth to children, they will remain vulnerable, meaning emotionally or physically insecure. Therefore, they feel the need for security, not just physical, but also financial, and this security can only be provided by a man.’

on why Elizabeth Bennet is considered the ‘loveliest’ heroine in fiction:

‘Natasha [from Tolstoy’s War and Peace] may have become old, ugly, and fat, but Elizabeth will remain young forever’

on adaptations and their merits (or lack thereof):

‘The most disturbing thing in this series is that imaginary beings like robot monkeys, clown banditos, zombies, werewolf zombies-ninjas-sea pirates have been pushed into novels.’

‘The first and most popular and famous novel in this series, published in 2009, is Seth Grahame-Smith’s “Pride and Prejudice and Zombies.” Its cover, which is very loud and horrific, depicts a beautiful woman wearing a blood-soaked gown, immediately attracting buyers […] Grahame-Smith believed that people are completely ready for gore and meaningless violence’

[These translations were conducted using Google lens. If you speak Urdu and have a more accurate translation you would be happy to contribute, please do get in touch!]

The immediate misogyny in these words is startling. It points to anxieties about women’s growing independence in Pakistani society, with the reassuring caveat that they will always be ‘vulnerable’, and that this vulnerability makes male strength and dominance necessary. It praises Elizabeth Bennet’s youth, beauty, and even her figure, dismissing other literary heroines as ‘old, ugly, and fat’.

More amusingly, perhaps, is the anxieties that the introduction of ‘zombies’ have provoked. The writer invokes not just zombies but ‘robot monkeys, clown banditos’, and ‘werewolf zombies-ninjas-sea pirates’ as horrors that have come to terrify and titillate a general reading public. Interestingly, the writer does not claim that these ‘ninjas’ and ‘sea pirates’ are widely disliked. He instead seems disturbed by the ‘immediate attracti[on]’ of a general reading public to this proliferation of violence.

For Austen is well read and loved in Pakistan – with or without the zombies. This particular edition was donated to Chawton House by Laaleen Sukhera, an author and founder of the Jane Austen Society of Pakistan. Alongside other women from the society, she wrote and edited a collection of Austen-inspired short stories set in Pakistan, Austenistan. Her fascinating discussion of the Jane Austen Society of Pakistan in The Routledge Companion to Jane Austen explores what makes Austen so attractive to modern day Pakistani readers.2 Through interviews conducted with a variety of Pakistani Austen fans, scholars, and writers, she tracks the strong appreciation of Austen by her global readers. She shows Austen’s regard in Pakistan to be a combination of her beloved and vivid characters, the relatable themes of the influence of family on courtship and marriage, and the sharp social satire and free-spirited heroines that attract so many readers across the globe. Alongside this, she shows how Pakistan’s colonial past – in particular, the imposition of ‘English literature’ that occurred under the British empire – has shaped her reception today.

So, in a curious melee of cultural attitudes, popular portrayals, and patriarchal censure, Austen’s writing has room to be portrayed as both safe, conventional and traditional, and as dangerously disruptive, even violent. It also contains the possibility for endless reworkings – Austen with zombies, Austen in Pakistan – with numerous Austen-dedicated fanfiction sites to show for it. What historical trends have influenced her reception? How do current readers imagine Austen? What about the future of Austen readers and scholars? What countries will she reach next, and how will she be imagined there?

Overall, then, introductions can be seen to make strong claims about Austen’s presence, talent, and importance, that might influence how a reader approaches the text. But clearly, the reception of Austen in a given country stretches beyond how she is presented in published translations, because Austen fans have long given her texts their own lives, meanings, and significance quite apart from the formalised publishing industry. In this respect, it is important to be mindful of the ways that individual readers, as well as collective reading cultures, impact Austen’s legacy. Informal fan groups, Austen-inspired creative works, and vibrant fan cultures work in parallel with the formal literary and translation market to shape Austen’s global reception.

Losing the Plot: A Selection of Blurbs

The job of a blurb, to summarise the main points of the plot in a way that draws in readers without giving away too much, leaves room for much oversimplification. Below are a few blurbs that cover the events of the plot, and Austen’s life and legacy, in surprising ways.

This Dutch edition opts for a sentimental and somewhat reductive overview of the plot, describing Pride and Prejudice as ‘a romantic love comedy about happiness and how it might be found’. The triteness of this summary illustrates how Austen has often been conceived of as a writer of ‘romance’ for women, unconcerned with politics or public life. The blurb also namedrops Keira Knightley, providing details about the cast of the 2005 film, often used as a marketing tactic in editions of the early 2000s.

This blurb, from a Romanian translation, echoes what many other blurbs, introductions, and biographies like to repeat: that Elizabeth Bennet represents an incarnation of Jane Austen herself. ‘The central character is largely autobiographical’ claims Dan Grigorescu, and Austen ‘attributes obvious self-portrait features’ to her. The extent to which Austen truly felt herself to be like Lizzy is unknowable today, but presents a catchy way of characterising Austen to appeal to readers.

This Norwegian translation is much more harsh on Elizabeth Bennet, steamrollering the nuances of the plot to claim that upon their first meeting, she ‘decides to dislike [Mr Darcy] despite the fact that he is both handsome and attractive’. This ‘foolishness’ is sharply censured here, as though to suggest that Lizzy will have to learn the error of her ways, rather than emphasising Mr Darcy’s character growth over the course of the novel.

This Polish edition contains perhaps the most damning summary. ‘”Pride and Prejudice” is considered a masterpiece’, it claims, ‘thanks to its humorous, almost Dickensian’ handling of character. This comparison damns her with faint praise, and shows how female accomplishments are often read only against previous male success.

This Polish edition, like the many others seen throughout, demonstrates how female authors often sit uncomfortably on the edge of the canon: accepted as ‘great’, but rarely on their own terms. The ‘almost’ here in ‘almost Dickensian’ reads more as a slight than as true praise, suggesting that her fame is due to her similarities to better, crucially male, authors. It is also strangely anachronistic, blurring the lines between Regency and Victorian novels (as previously seen on some of the cover art).

Mostly, the adjective ‘Dickensian’ is telling. It speaks to the ways in which the dominant culture – male, patriarchal – seeks to name and label things after its own fashion, i.e., to do with men. Orwellian, Shakespearean, Dickensian, Kafkaesque… rarely are literary achievements named after pioneering women authors. Austen is one of the rare female writers that gets an adjective of her own (sometimes Austenian, sometimes Austen-esque), though this edition forgets this. Here, her work is only as good as it is similar to Charles Dickens. Often, even the brand of Austen isn’t enough to portray her as brilliant on her own terms.

Conclusion: The Incredible, Imaginary Jane

Once again, this project produces more questions than it can hope to answer. But I hope this selection of portrayals of Austen, from all over the globe, proves thought-provoking and worth further investigation. Around the world, each different translator, editor, publisher, and most of all reader, continues to shape the ‘Jane Austen’ we know today. She is multifaceted, multiplicitous: able to be read, understood, and celebrated by a diverse array of cultures and people. The paratextual presentation of her novels both shapes her popular reception and allows us to fruitfully investigate how she has been imagined. How will a new generation of readers and translators encounter her?

As ever, I am keen to hear any thoughts or suggestions. Don’t hesitate to get in touch! This page, along with the website, will continue to be updated as the project develops, so check back soon for more.

- Git Claesson Pipping and Eleanor Wikborg, ‘Jane Austen’s Reception in Sweden’, in The Reception of Jane Austen in Europe, ed. by Brian Southam and Anthony Mandal (Continuum, 2008), pp. 152-168 (p. 153-55) ↩︎

- Laaleen Sukhera, ‘Global Jane Austen: Obstinate, Headstrong Pakistanis’, in The Routledge Companion to Jane Austen, ed. by Cheryl A. Wilson and Maria H. Frawley (Routledge, 2022), pp. 468-80 ↩︎