HOW HAS THE WORLD READ JANE AUSTEN?

In the 250th birthday year of Jane Austen, I reflect on what makes such a quintessentially ‘English’ novelist a global celebrity…

“It was a sweet view — sweet to the eye and the mind. English verdure, English culture, English comfort, seen under a sun bright”

Emma, 1816

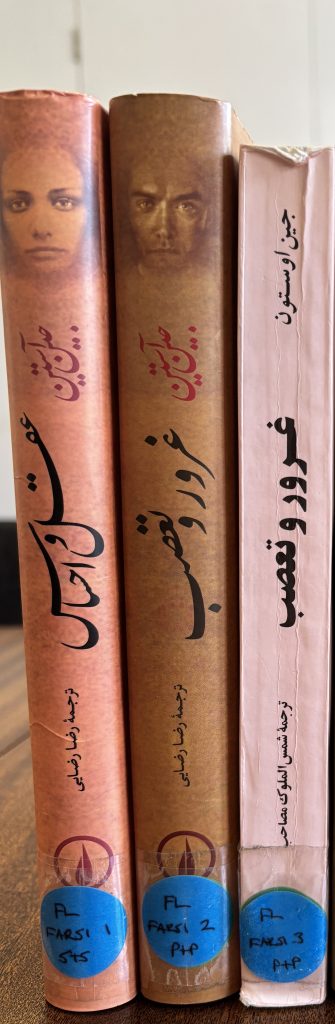

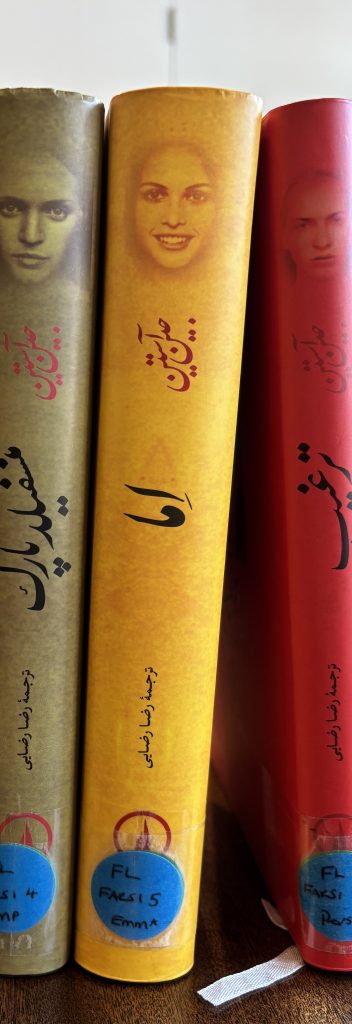

So claims the narrator of Emma in chapter 42. And ‘sweet’ indeed has English culture seemed to an international audience – sweet enough that Austen’s novels have been translated into over 40 languages worldwide, the first of which appeared during her own lifetime (though she was likely unaware of this).12

Austen herself was not credited in any of the earliest translations until 1821, with Isabelle de Montolieu’s French translation of Persuasion, entitled La Famille Elliot.3 Since then, she has been rendered with various names – Jeanne Austen, Johanna Austen – and her plots have been variously misconstrued, expanded upon, or cut down severely. As scholars, enthusiasts, and readers, now is the time to consider her global legacy, and how the world reads Austen.

Data on translations of Austen’s works could be synthesised into a searchable database, allowing readers to explore her global reach and the spread of her novels around the world. In what year did Austen come to France? To China? To India? Where are the peaks in translation activity, and why do they occur? What of retranslations, where a translator worked not from the original text but from a previous translation? What can these tell us about cultural and linguistic connections across the globe?

A digital humanities project could shine a light on the early translators of Austen’s works, often women, who took her texts and ran with them in all kinds of fascinating ways. What else were these translators translating? How did they interact with the publishers and other players in the literary marketplace?

Interactive maps would allow readers to explore, say, the publishing houses of nineteenth-century Paris, or plot the first translation of every country in Europe.

This website makes a start on all of these ideas, as I investigate what is possible, practical, and useful to record of Austen’s translations. Crucially, I want this to be a project for all. The idea is to start with a database that could be of use to for researchers and teachers at all levels, and to test how such data could be presented to be accessible and of interest to fans and readers.

I have been inspired by book/manuscript studies approaches alongside digital humanities techniques. The resulting project is a glimpse into what might be possible to achieve when thinking about the history of translation of Austen. I am conscious that this is not the whole story – of course more translations exist, and will need cataloguing, in due course.

This is a collaborative project. I have already consulted with some translations experts and Austen scholars worldwide, thanks to the University of Southampton’s Global Jane Austen conference. And I value your input, too – please see the Contributions section if you have any information, notes, or comments you would like to share.

My Visit to Chawton

During the course of this research project, I had the privilege of visiting the village of Chawton, only a short drive from Southampton, where Austen lived for the last 8 years of her life. Both Chawton House, her brother’s estate, and Jane Austen’s House, the cottage where she lived, hold collections of translations that have been donated by translators and fans from around the world, which I was able to view and photograph for the project. More information about the collections in Chawton can be found on the ‘Maps’ and ‘Illustrating Austen’ pages.

- Jane Austen’s House, https://janeaustens.house/ ↩︎

- The Reception of Jane Austen in Europe, ed. by Anthony Mandal and Brian Southam (Continuum, 2007) ↩︎

- Lucile Trunel, Les éditions françaises de Jane Austen 1815–2007: L’apport de l’histoire éditoriale à la compréhension de la réception de l’auteur en France (Paris, 2010) ↩︎