What else can the data tell us? See below for charts and graphs produced from the dataset that have interesting stories to be investigated.

See the ‘Database’ page to learn more about where the data comes from, why I’ve chosen to collect it, and what its limitations are.

The Impact of Adaptation

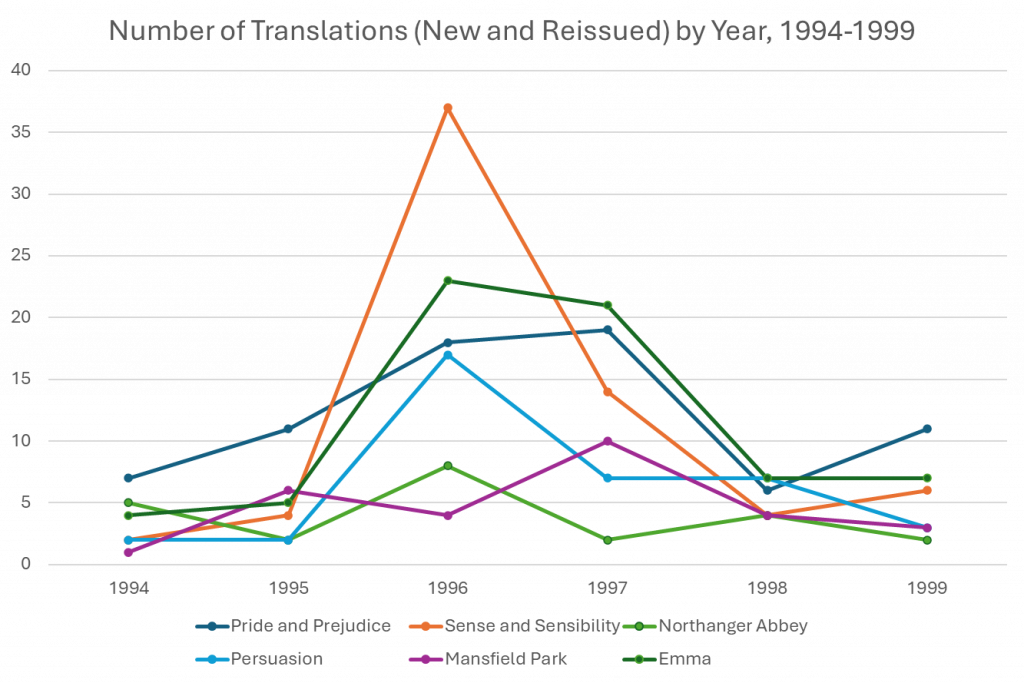

This chart maps the number of translations for each novel, both new and reissued, each year from 1994-1999. Immediately obvious is the large peak in 1996, not just for Sense and Sensibility but for most of the other novels as well. So how to explain this?

The answer lies in the booming popularity of Austen as a cultural figure in the 1990s, brought on by multiple book, film and tv adaptations of her works. They are:

- 1995: Ang Lee (dir.), Sense and Sensibility (film)

- 1995: Amy Heckerling (dir.), Clueless (film – loosely based on Emma)

- 1995: Andrew Davies (dir.), Pride and Prejudice (tv)

- 1995: Roger Michell (dir.), Persuasion (film)

- 1996: Douglas McGrath (dir.), Emma (film)

- 1996: Helen Fielding, Bridget Jones’s Diary (novel – loosely inspired by Pride and Prejudice)

- 1999: Patricia Rozema (dir.), Mansfield Park (film)

The collective star power behind these films – Kate Winslet, Emma Thompson, Alan Rickman, Colin Firth, and Gwyneth Paltrow, to name a few – brought Austen’s novels to renewed public attention and appreciation. Many, like Ang Lee’s Sense and Sensibility and BBC’s TV Pride and Prejudice, were global hits that produced a massive spike in global cultural awareness of Austen. The dramatic increase in published translations of Austen’s novels correlates closely with the boom in film productions. Indeed, a look at book covers from this era shows the proliferation of editions of Sense and Sensibility fronted by Emma Thompson and Kate Winslet. In France, Isabelle de Montolieu’s original ‘translation’ – in reality, more of a freewheeling adaptation – was reissued with a still from Lee’s film on the cover. This unlikely pairing demonstrates both the drive to get editions of Austen in translation into print (no matter the quality), as well as the the marketability of the films.

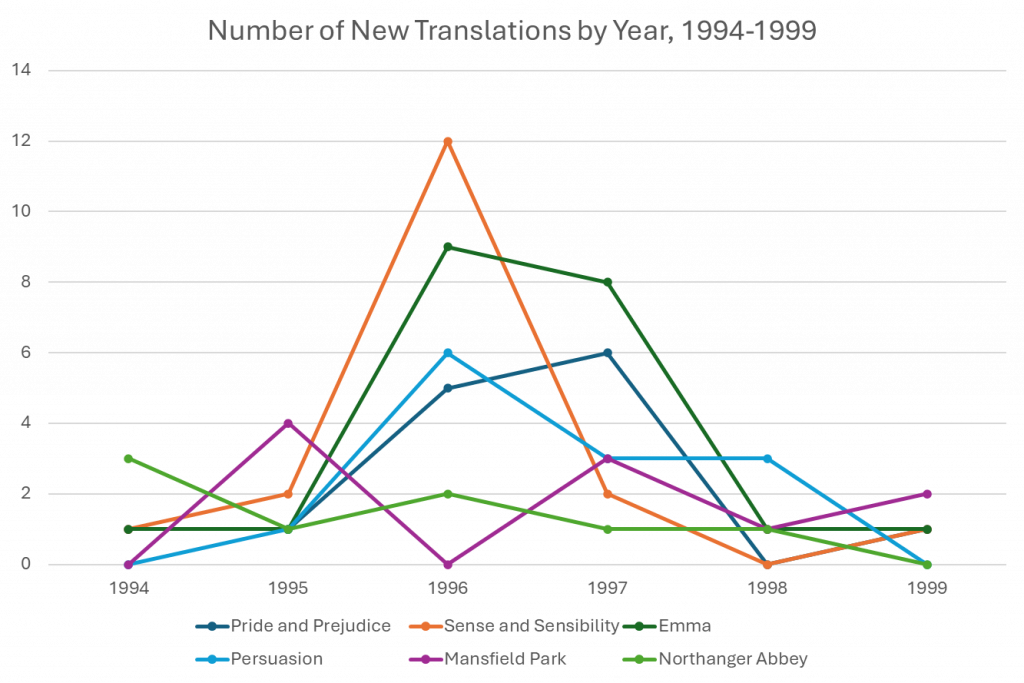

This graph shows the new translations – i.e., not reissues – published each year. Even without taking into account republished translations, the pattern remains strong, from very few translations in 1994 to a sudden spike in 1996 that affects most (though not all) of the novels.

Interestingly, there is a definite drop in translations in 1998. I would suggest that this does not simply reflect a decline in Austen’s popularity, as she has only grown in influence since the mid-90s. Rather, I would suggest that the proliferation of translations from 1995-96 would have rendered further new translations unnecessary for the next couple of years.

The story of course does not end here – just as the story of the adaptations does not end here. Far from a brief surge in popularity followed by a decline, Austen’s global presence is, today, stronger than ever. Currently, the database records at least 26 different countries of publication and 23 different languages, and it is far from complete. Jane Austen’s House estimates the true number of different languages to be at least over 40.1 At present, the number of recorded translations is highest in the database for Pride and Prejudice, which is often considered her best known novel – but that may change as more data is collected.

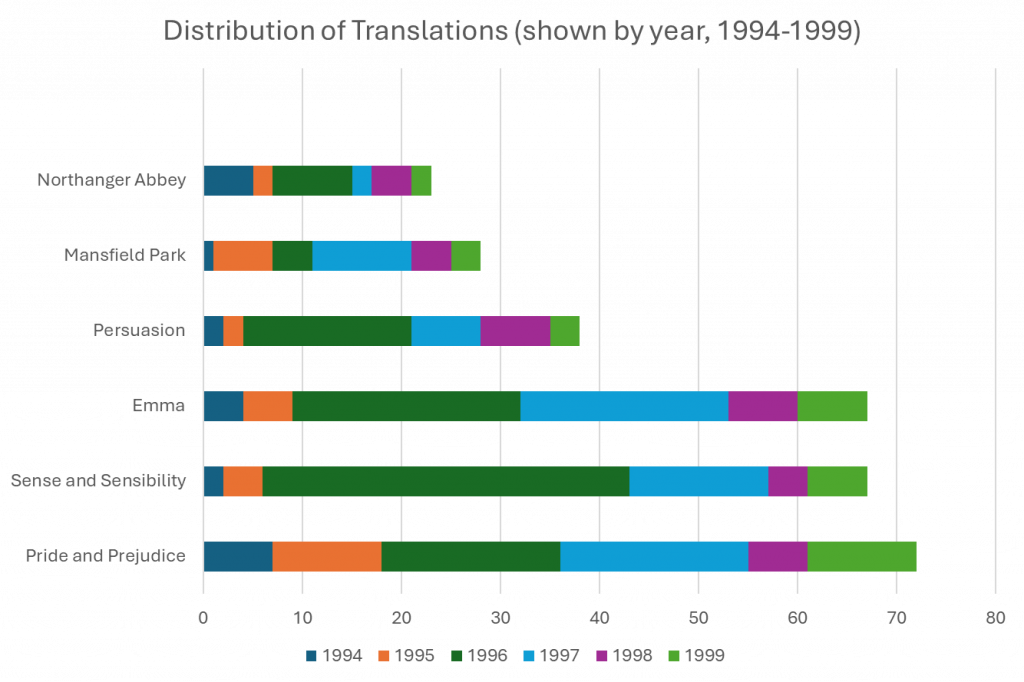

This graph shows the total number of translations for each novel, separated by year. Though Northanger Abbey, Mansfield Park, and Persuasion lag behind, their numbers are hardly insignificant. In future, this project aims to record as many translations as possible. What will the data show then? How will the impact of, for example, the 2005 Pride and Prejudice film starring Keira Knightley affect the translations? In the ‘Illustrating Austen’ section, the gallery of cover images clearly shows the proliferation of Keira Knightley’s face used to market Pride and Prejudice. So what more is there to discover? Like many questions we might ask of the data, these remain unanswered for now.

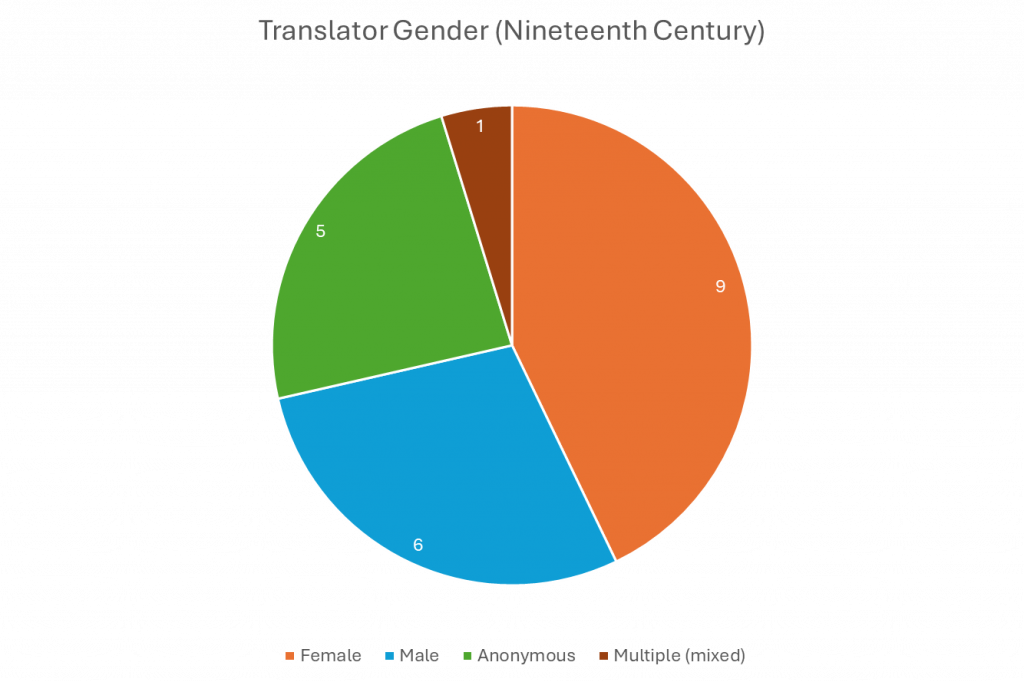

There is, however, more data to investigate for the nineteenth century, which, on a much smaller scale, can give us an insight into how the earliest translations circulated.

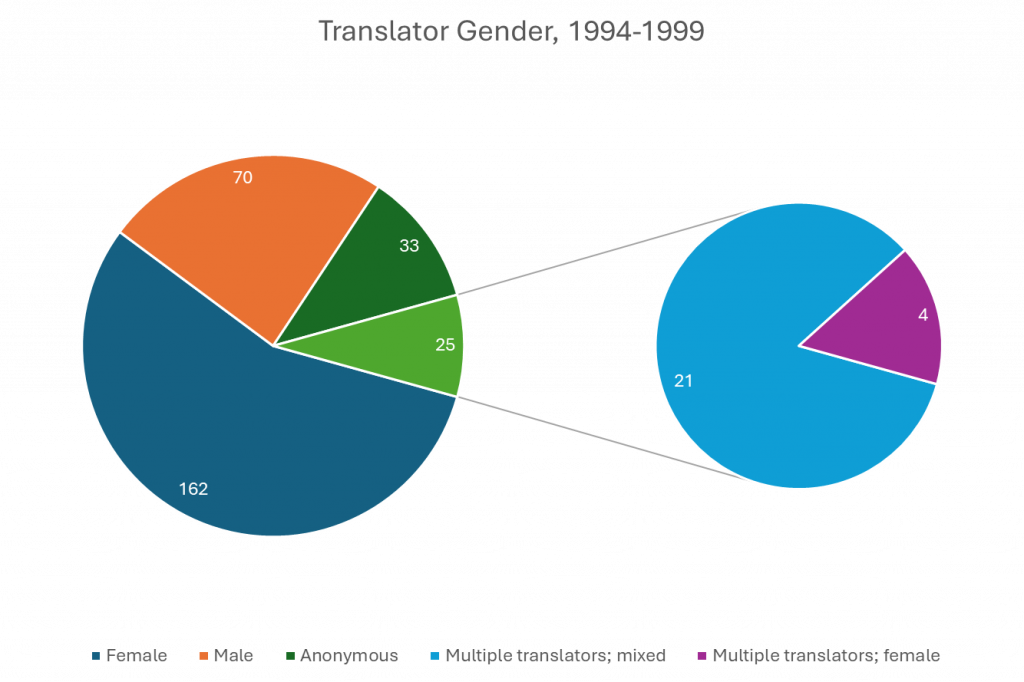

This chart shows some information about the identity of Austen’s very earliest translators in the nineteenth century. Predominantly, those translators were women. There were also many published anonymously – and some who were originally anonymous, but whose names and genders we now know. The chart below provides the same information for the 1994-1999 translations, where some of the same patterns are clear.

Again, the number of editions by female translators far exceeds those of male translators. The second pie chart shows that there are no groups of multiple translators that are male-only. And there is still a clear proportion of translations by anonymous translators. For example, as Cinthia Garcia Soria examines, there were a surprising number of anonymous Spanish translations published in the twentieth century, due ‘stolen translations’ and publishers attempting to avoid copyright laws.2 This might explain why even in an age where translation work is more valued, anonymity can still be problematic.

Some early translations didn’t even record Austen’s name, let alone that of a translator. The fame of her first full translator, Isabelle de Montolieu, eclipsed her own fame in France to the extent that Montolieu’s name alone appeared on the covers. And many subsequent translators, perhaps unaware of Austen, translated not from her original texts but from Montolieu’s very free French translations – often falling more under the label of adaptation than true translation. For example, the first Swedish and Portuguese translators of Persuasion, Emilia Westdahl and Manuel Cota d’Araújo, gave their translations the titles ‘Familjen Elliot’ and ‘A família Elliot’, following Montolieu’s ‘La famille Elliot’ rather than ‘Persuasion’, and are listed as translations from the French.3 4

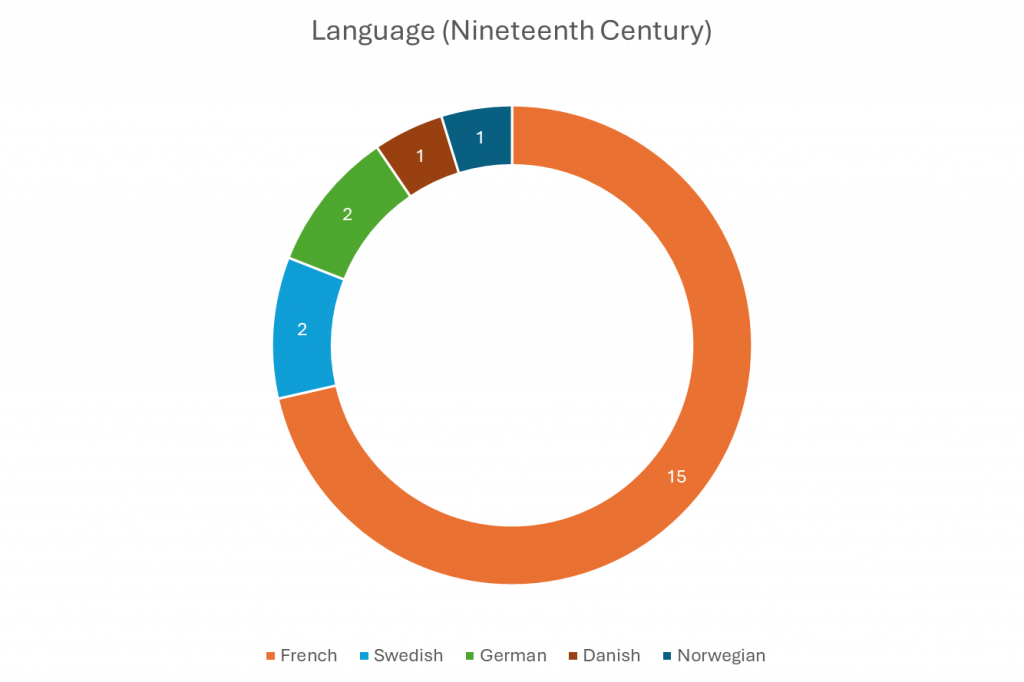

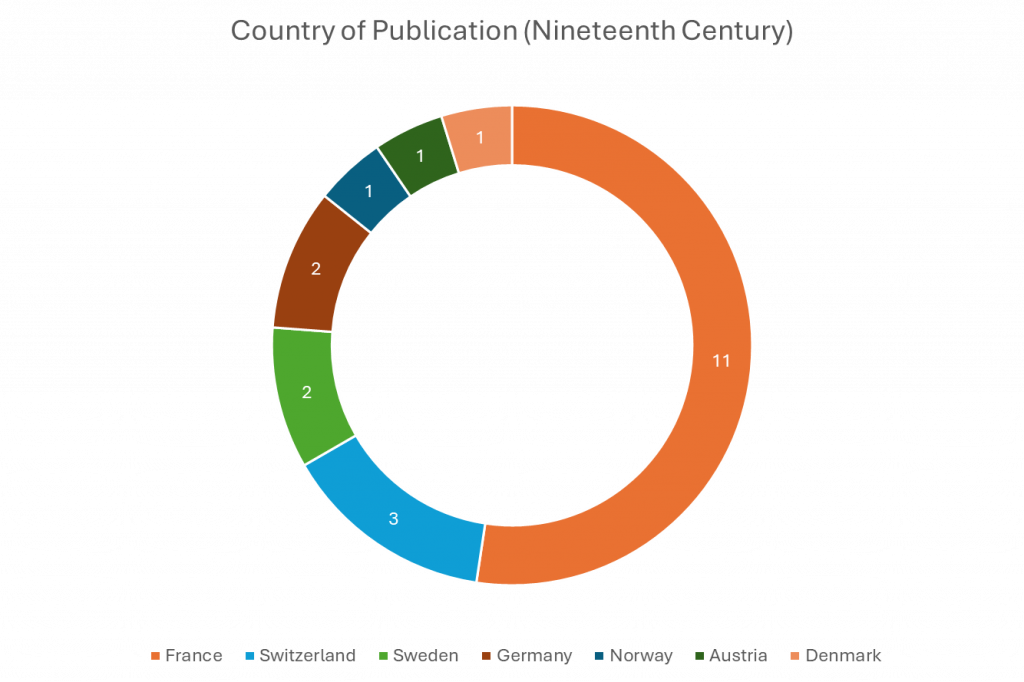

Below you can see an overview of the languages and countries of publication during the nineteenth century.

What the data shows above all is the cultural and literary interaction taking place across Europe – and further, across the world – in the nineteenth century. There are more distinct countries of publication than languages, indicative of the plurality of languages spoken across Europe, e.g. by French speakers in Switzerland and Austria. For example, the very first translation of Austen’s work, extracts from Pride and Prejudice in French, was published in Switzerland.

Importantly, though on first glance it appears that Austen did not travel outside of Europe in this era, Sandra Vasconcelos has recently proven otherwise. Manuel Cota d’Araújo’s Portuguese Persuasion (published without credit to Austen or even to Montolieu) had travelled no small distance to bookshops in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, by 1858.5 This is the start of Austen ‘going global’, perhaps not as her original English readers knew her, but still global, as book trading and cultural exchanges brought readers into contact with texts in translation. Thus, tracking early translations of Austen’s novels paints a picture of a culturally and linguistically interconnected Europe (and world), where texts could spread in curious ways between cultures.

These are just some of the more interesting insights that the database has to offer. You can investigate for yourself by navigating to the ‘Database’ page. As Austen has moved further out of Europe and across continents, she has been encountered by a diverse array of readers, all of whom have different cultural perspectives to bring to her work. Even an English reader would nowadays struggle to understand the ‘white soup’ prepared in Emma, for example – so how would a reader from China interpret it? What about Azerbaijan? Reading Austen after her time can be challenging. So how did one keen translator manage to translate Pride and Prejudice into Latin, a ‘dead’ language spoken hundreds of years before Austen?

For deeper exploration of how readers have read, interpreted, and perceived Austen, see the Imagining Austen feature.

This project can only hope to spark new ideas and questions, by way of showing what might be possible to record and investigate, and where this might lead in our explorations of the global influence of a much-loved English author. If you have any ideas, comments, or questions, please get in touch! I would love to hear your thoughts on the project’s progress, and where it could head next. You can get in contact through the ‘Contribute’ button in the side bar on the homepage. See below for references, or the Bibliography page for a full list of sources.

- Jane Austen’s House, https://janeaustens.house/object/danish-translation-of-pride-prejudice/ ↩︎

- Cinthia Garcia Soria, https://jasna.org/publications-2/persuasions-online/volume-43-no-1/garcia-soria/ ↩︎

- The Reception of Jane Austen in Europe, ed. by Anthony Mandal and Brian Southam (Continuum, 2007) ↩︎

- Maria Biajoli, https://jasna.org/publications-2/persuasions-online/volume-40-no-1/pivato-biajoli/ ↩︎

- Sandra Guardini Teixeira Vasconcelos, ‘Circuits and Crossings: The Case of A Família Elliot’, in The Transatlantic Circulation of Novels Between Europe and Brazil, 1789–1914, ed. by Márcia Abreu (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), pp. 125–44 ↩︎